Raising Young Upstanders from the Start: Advice From a Preschool Leader and Mom

For young children, the classroom is a community: a small version of the world.

As such, it is too often a place in which there is inequity, unkindness, and bullying among peers — and it’s also a place where children can practice being upstanders who stand up for friends.

Bullying remains pervasive in school settings. Some recent facts:

- 20.4% of children ages 2-5 had experienced physical bullying in their lifetime and 14.6% had been teased (verbally bullied) (source)

- About 1 in 5 U.S. students aged 12-18 say they have experienced bullying (source)

- Children say they’re being bullied in school hallways or stairwells; classrooms; cafeterias; bathrooms; and playgrounds (source)

As the director of a progressive preschool program and as the parent of a kindergartener, I deeply feel the need to help my child — and the children in my school — grow into empathetic friends who can stand up for what they believe is right and be “upstanders.”

The idea that everyone deserves to be treated fairly and kindly is the heart of social justice, and preschools often work to put these values at the heart of their curriculum. These are skills that must be learned early, to help children grow into empathetic and kind adults, who will stand up for those not being treated kindly or fairly.

We All Have a Role to Play in Creating a Culture of Upstanding

Teachers have an active responsibility of ensuring safety, kindness, and equity in classrooms, and parents also cultivate these skills at home.

Learning to be an upstander ties together a lot of social and emotional skill “basics” like feelings, empathy, friendship. It’s something that we can start teaching when children are as young as two — and it is something we can practice throughout our lives.

While learning to be an upstander can take work — it makes a difference: Research shows that when children stand up for each other, and are active when they witness bullying, this involvement is hugely effective in curbing the behavior. When upstanders intervene (child to child), bullying behavior stops within 10 seconds 57% of the time (source).

Start with Feelings and Empathy

How do we encourage young children to grow into upstanders — people who will stand up for what is right and help peers feel safe and welcome?

For the very young, it begins with digging deeply into first noticing the feelings of others, and growing empathy.

For very young children (ages 2-4), the idea of standing up for other people will, at first, be beyond their grasp. Children at this age — by nature — have a very ego-centric view of the world. As they move through the preschool years, they develop the neural connections to be able to see the world from another’s perspective, and understand that others have feelings that may be similar or different from their own.

Raising upstanders begins with growing empathy and cultivating the urge to help when someone else is feeling sad or having other uncomfortable feelings.

At our preschool, social-emotional learning is an integral part of the curriculum. For two year olds, it begins very simply — when navigating conflict, teachers offer simple language, and encourage children to notice how their actions affect their peers.

For example: “Look at Sarah’s face. She looks so sad. She didn’t like it when you pushed. Let’s go get her an ice pack to help her feel better.”

Soon, teachers notice children responding to others in need, offering a friend a tissue, their lovey, or patting their back gently when they notice someone having a hard moment. Even two year olds are familiar with the warm feeling that comes with helping someone else.

The three- and four-year-old students at our preschool spend time actively learning about feelings as a curriculum theme. Group discussions are a way for children to build their own understanding on a theme by using each other as resources.

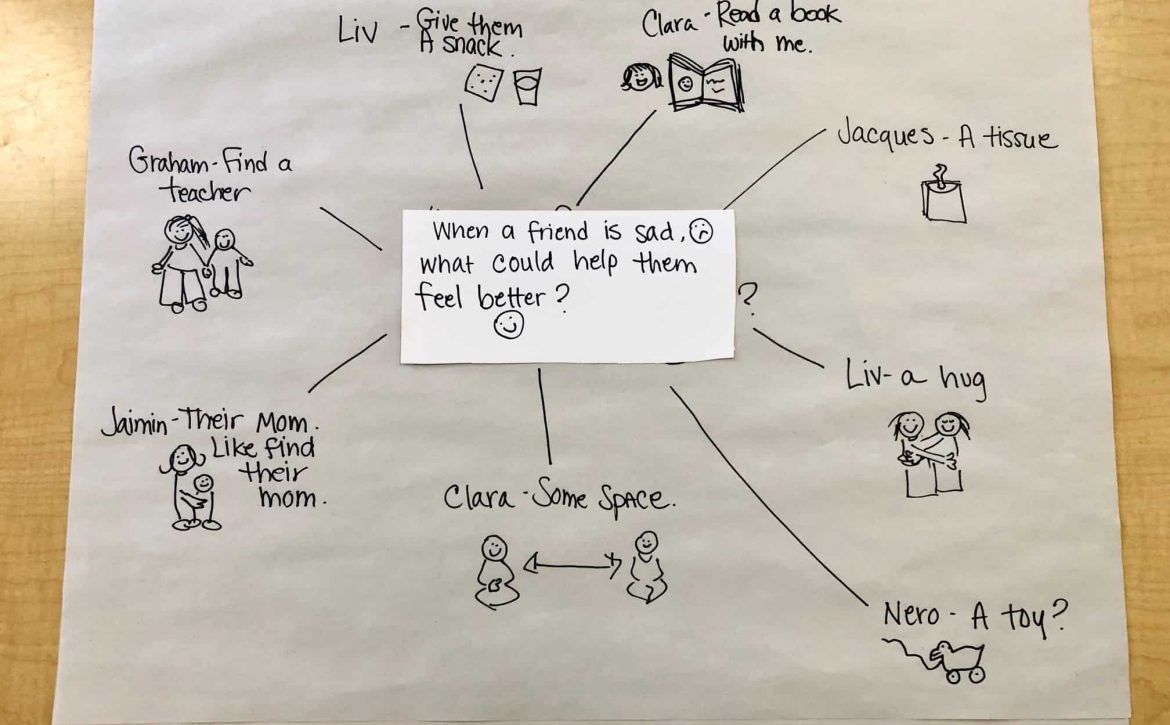

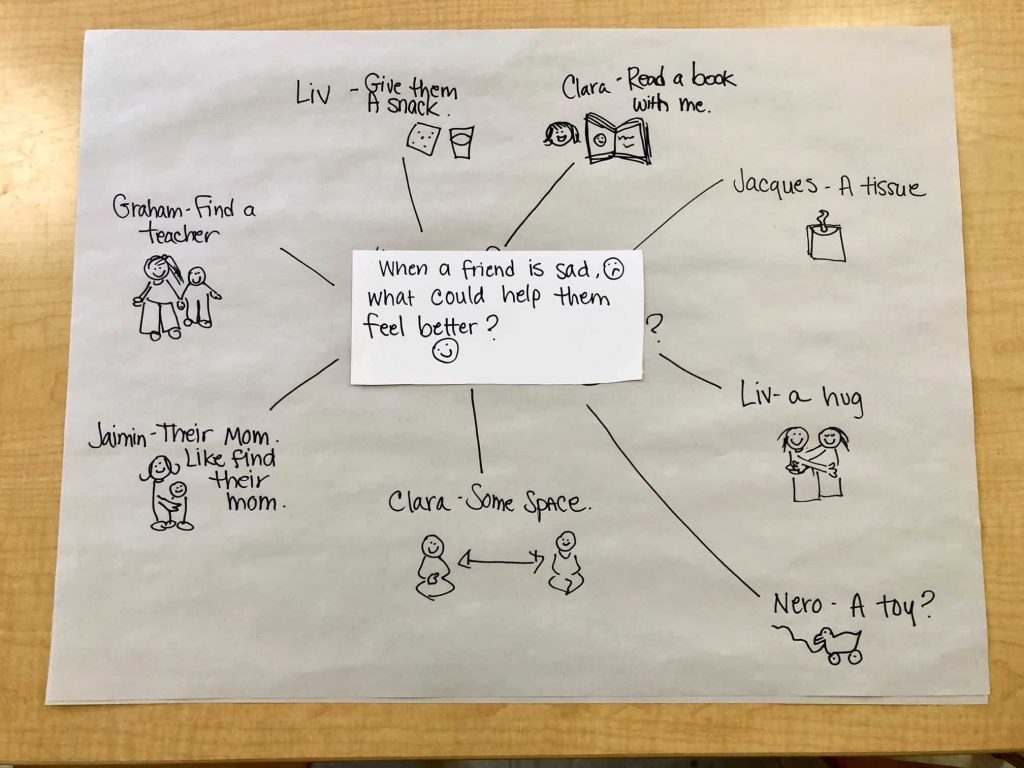

During a recent feelings study in a 4s classroom, a teacher asked the group at morning meeting: “When someone is feeling sad, how can we help them feel better?”

Children had many ideas:

- Child: “They might need a tissue!”

- Child: “A hug.”

- Teacher: “Mmm. Who else has an idea? How can we help a friend who is sad?”

- Child: “Go find a teacher?”

- Teacher: “A teacher can always help children when they’re feeling sad.”

- Child: “Maybe they miss their mom.”

- Teacher: “Do you think that’s why they’re sad? What do you think would help?”

- Child: “Maybe to see their mom. Or hold their family collage?”

- Teacher: “Ah, yes! Those usually have pictures of grownups from your family.”

- Child: “Sometimes I miss my mama.”

- Child: “Sometimes I miss my grandpa”

- Teacher: “It sounds like a lot of children feel sad when they’re missing their families.”

In this conversation, children were ready with ideas about how to comfort or care for someone. When they found common ground (many children thought about missing their family), the teacher noticed and reinforced the idea that many children can have that same strong feeling.

The teacher recorded children’s ideas with an idea map, including illustrations of different strategies to comfort or help a friend.

This image will stay on their classroom wall throughout the year, an easy reference when children were engaged with each other in the classroom.

Learn From Examples Through Upstander Stories

As children develop the ability to empathize and think outside themselves in the 4s and 5s, they also often become interested in the world around them, and the non-fiction section of the bookshelf becomes enticing.

This age is perfect to introduce simply books and biographies about people in history who are “upstanders,” those who noticed unfairness and inequity, and who stood up for those who weren’t treated with kindness and fairness.

There is a growing set of wonderful picture books that help children think about inclusion, friendship, and how to support their peers. Some great ones to start with include:

- Martin’s Big Words: The Life of Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. by Doreen Rappaport

- We are the Water Protectors by Carole Lindstrom and Michaela Goade

- Little People, Big Dreams: Nelson Mandela by Maria Isabel Sanchez Vegara

- Malala’s Magic Pencil by Malala Yousafzai and Illustrated by Kerascoët

- The Big Umbrella by Amy June Bates and Illustrated by Juniper Bates

- Mushroom in the Rain by Mirra Ginsburg and Illustrated by Jose Aruego

- Strictly No Elephants by Lisa Mantchev and Illustrated by Taeeun Yoo

- All Are Welcome by Alexandra Penfold and Illustrated by Suzanne Kaufman

These stories serve as a jumping off point for rich conversations about justice, fairness, and how we can help make the world a safer, more equitable place.

After my own little boy read Martin’s Big Words with his 4s class, they discussed the story as a class. Their teacher talked in simple terms about the civil rights movement. The teacher helped tell the story with the aid of a toy bus and some figures with light and dark skin.

My child brought up the book and class discussion often at home, at first talking about “back when things weren’t fair.” We talked about how things were still not fair, referencing our family’s recent participation in a Black Lives Matter protest. He continued thinking through it in the coming weeks, asking questions like, “What other things are unfair for people with brown skin?” and “Why?” Parents and teachers might not have the answers to these big questions, and that’s OK! Sometimes the question “What do you think?” is enough to continue a dialogue that will grow and change as the child does.

Making a Plan and Providing Language

As adults talk through big ideas with children and allow them lots of space for their own ideas, they’re helping them to learn the language they’ll need to address bullying and become upstanders.

As children enter the 4-6 range, they are more and more capable to become upstanders among their peers. Sometimes that means simply modeling kindness and inclusivity themselves — inviting someone into a game, or sitting with them at lunch.

It can help to create a simple script with your child, so they are ready and know what to say when a situation pops up when they see someone being bullied. This conversation may happen out of the moment, or in response to a situation that a child is processing.

My child reported one day, “W. bumped C.’s ear, and it was not an accident, and the teacher didn’t know!”

I started by acknowledging how it must be feeling for everyone involved. “It sounds like it made you so mad to see your friend get hurt. Was C. sad? Is he OK now?”

I asked, “What do you think you could do next time to help your friend?” He suggested finding a teacher. Especially at this age, it’s wise to reinforce that this is ALWAYS a smart option when someone is hurt. We also practiced what my child could say, words such as:

- “Don’t Do That!”

- “That’s too rough!”

- “Stop!”

Having a script in mind helps children feel like they are ready to help, with a toolbox of effective words.

Sometimes adults shy away from talking about conflict with young children — as parents and educators, we wish that the world were always fair. It can be hard and sad for us to have those conversations with kids. But we can empower our children by making them part of the conversation, giving them the language to talk about feelings, and sharing tools with them that they can use to stand up for thief friends and be confident in caring for those around them.