How do we proclaim our love for one another?

On February 14, the pressure is on to figure that out — and for some people (young and old), this can be stressful. How do I put what I feel into words? How do I find the perfect gift to symbolize my complex feelings? What’s a meaningful way to show my feelings?

As we consider how Valentine’s Day can feel for adults, many parents and educators wonder how we might recalibrate this holiday for young children. After all, love is an important feeling; we want to help our children identify love and show love to family and friends — but we want to teach about love in a way that can support children’s developing social and emotional skills.

Leading up to Valentine’s Day, store shelves are lined with every possible pink and red heart-shaped candy, plus boxes of pre-made cards where parents can fill in each name from the class list. Leaving the very valid health concerns to a separate listicle, many parents and educators wonder: What’s the point and what’s the effect of the candy and canned message approach to Valentine’s Day? Most children certainly love to receive sweet treats, but do they actually show (and build) love and companionship?

Love and Kindness Happens in the Every Day

As an early childhood teacher and mother, my focus has been capturing authentic expressions of love and recognizing the moments when these neural pathways are forging, rather than focusing on one day on the calendar when we’re supposed to celebrate love.

It is often in the day-to-day that authentic expressions of love occur: When we’re reading together, helping our friends on the playground, sharing something we learned over lunch.

So how do we highlight loving interactions and create more opportunities for them that foster social emotional growth in a meaningful way — on Valentine’s Day and on the other 364 days of the calendar?

Five Authentic Ways to Celebrate Love that Teach Social and Emotional Skills to Young Children

Here are five ideas I’ve used as a mother and a teacher, which can be carried out by families as well as in a classroom setting:

1. BE THE NARRATOR

Caring moments are around us all the time. The key is to notice them and say them aloud. Think of yourself as the narrator of a child’s loving moments and be on the lookout for everyday expressions of love. Verbalizing and reflecting back acts of love increases our awareness of them as they occur as well as how they feel.

If you want to take your narration to the next level, you can create your own “love story” together. This can be a book very simply made by binding a few pieces of paper together by stapling or perhaps using a hole puncher and yarn. The title could be ‘I love you’ or whatever suits the author and recipient! Let’s imagine it is a book from a mother to her 3-year-old son: “Mommy loves you” (title page), “I love when you give me hugs” (page 1), “I love reading with you” (page 2), “I love holding your hand” (page 3). You can give this little book to a child and perhaps they would like to add some color to the pages with you! (This is totally optional; your child’s contributions should be natural and unforced.) They can have this book to read any time as a reminder of your love. In classrooms, teachers can help facilitate creating love stories!

A simple question such as, “Who do you love?” can be just the right prompt to invite children to think about their love for parents, pets, siblings, trees, etc. Teachers can write students’ words onto the pages of the book and children can be invited to add their own illustrations.

2. SET THE SCENE

Many children enjoy drawing and will often draw pictures saying “This is for Mama” or “This is for my Nanna.” Dedicate a table for these authentic love notes by setting out envelopes, paper (doily paper can be fun!), stamps, stickers, crayons, or anything else you might have on hand! Allowing materials to be varied as opposed to Valentine’s themed will allow richer artistic expression and more organic creations. A caregiver or teacher can sit with the children and offer language to go along with their work, such as “You are really thinking about mommy when drawing that picture. Mommy loves you so much!” or “I noticed you are using blue on your drawing for Papa, would you like to give it to him in an envelope?” or “You are putting so many stamps on Mama’s paper. You must love her so much!”

3. WIRED FOR LOVE

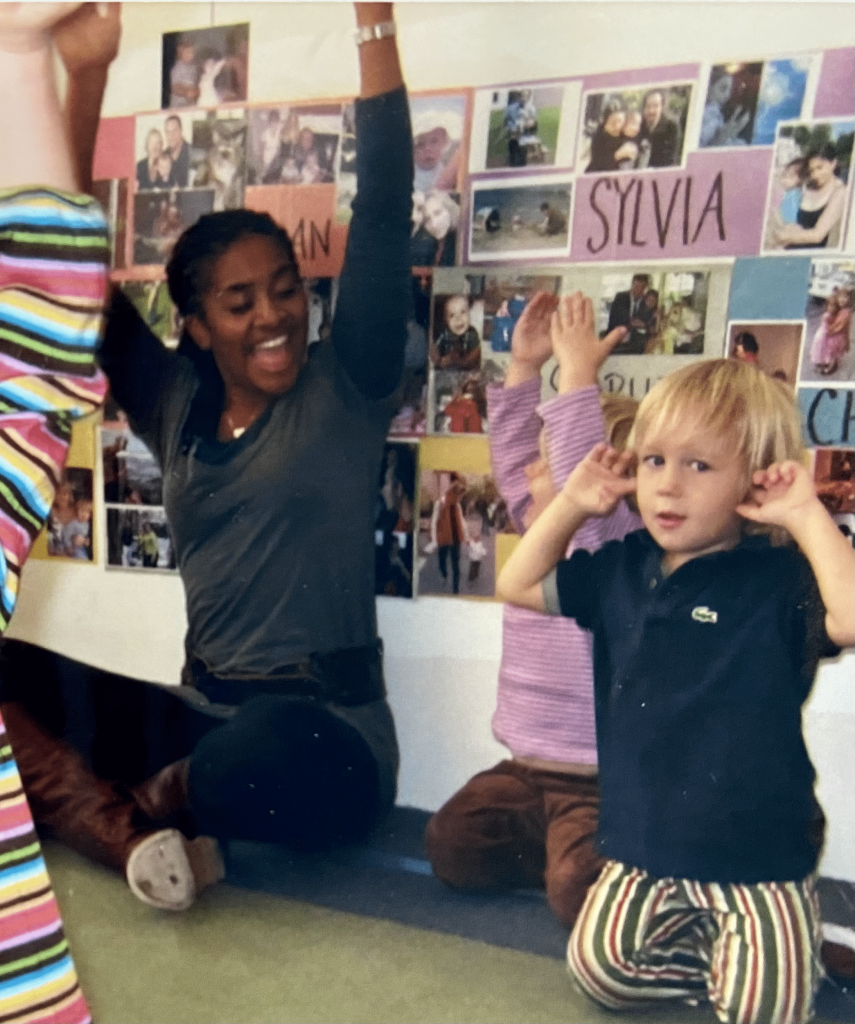

Part of creating the neural pathways for social-emotional development is through thinking about and recognizing feelings. This cognitive-emotional wiring is fostered by thinking about feelings as they are happening as well as reflecting on them afterward.

One way to “wire up” for social and emotional development is by creating a feelings board. Use whatever materials you have on hand: a large piece of cardboard, felt, or fabric can be the backdrop. Create a simple face drawing of each emotion: happy, sad, angry, tired, frustrated/grumpy, surprised. Cut them out and place each one along the top of the board and draw columns for each one. Give each child a way to sign up for the emotion they are feeling at any given moment. Perhaps this is done by having a cutout of each child’s name or by using a small photo of them and then using tape or a magnet if it is a magnet board, or by using felt names that will stick to fabric/felt boards. As children engage with selecting their emotions, grown-ups can offer language. Perhaps Sandra receives a hug from a friend and then proceeds to sign up under the “happy” face. Sandra’s teacher can increase her awareness by describing that event: “Sandra, when you got a hug from your friend, that made you feel happy.” Another example could be that Sandra’s block structure gets knocked down and then she goes and puts her name under the “angry” face. Her teacher can reflect back: “You are feeling angry about the block structure falling. I wonder what we could do about it to help you feel okay again?”

4. PEER LOVE

The “golden rule” has evolved and now it is more powerful to treat others as they wish to be treated. That means we need to become more aware of other people’s preferences and what feels good to them. Most children are keen to hone this skill! They often make observations about their peers such as which belongings are theirs (shoes, jackets, water bottles, stuffies, etc.!), recognizing the parents and family members of friends, and noticing what classmates like and do not like. Teachers and parents can use “narration” to highlight when we see children make connections with peers.

For Example: Tanya hears Holly say she is thirsty. Tanya gets Holly’s water bottle (having observed which one is hers) and brings it to her. Teacher says: “Tanya, you heard that Holly was thirsty and brought her water over to her! It looks like Holly is really drinking that water!”

For Example: A child trips and falls down. His sister comes over and begins to rub his back gently. The parent can highlight this by saying something like “Suzie, you noticed that Nigel fell. Did you come to check on him? I wonder if Nigel is OK? Suzie you are really taking care of Nigel and giving him a gentle rub on his back.”

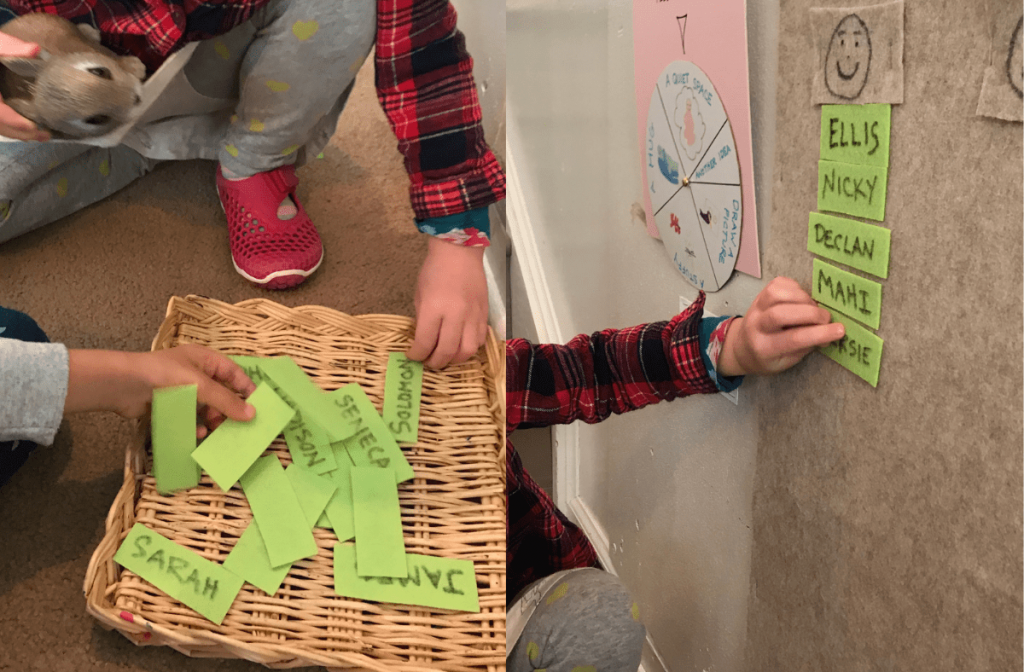

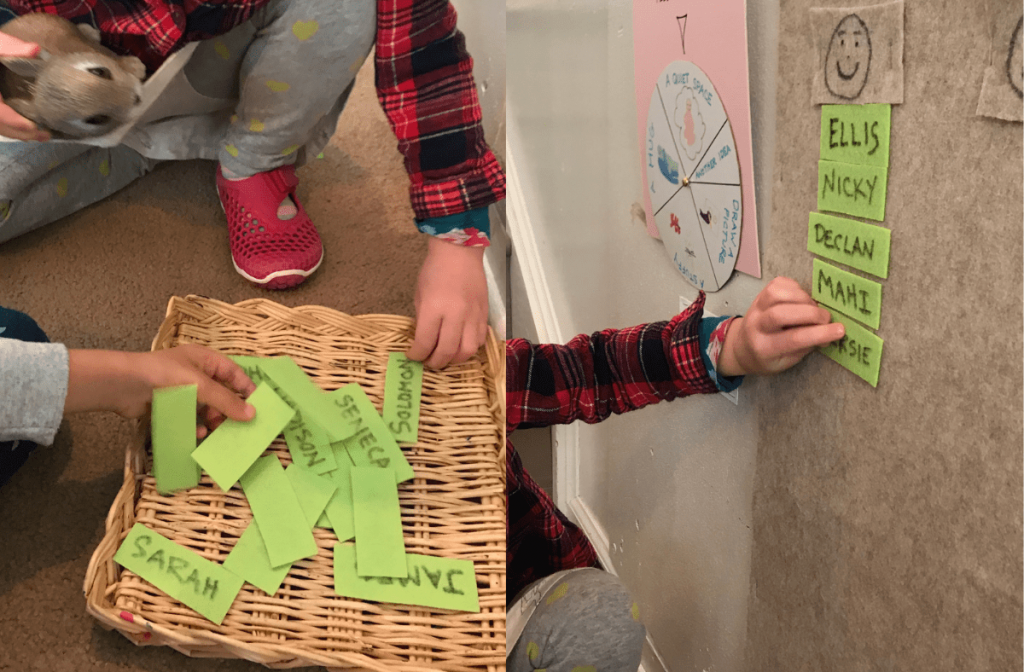

Parents and educators can prompt peers to interact with each other by creating opportunities for working together, share, and show their feelings. Here are two prompts to get you started — but many other activities would work, too:

- Valentine’s colors with Playdough. Make red colored playdough and offer it with red, pink, and white pipe cleaner, cut down to about half the length. Perhaps offer some small plates or cupcake liners for children to set their creations in. Children will often work with playdough and then offer it to someone (a caregiver or parent). Remind children that they can offer playdough creations to their peers as well. For example, a teacher or parent can say: “Luis, thank you so much for this yummy (playdough) cake. I wonder if Mica would like a piece. Shall we ask her?” This can spark connections between children and also show how we ask first what the other person would like.

- “Taking care of others” idea-share. Sit with children and think about the feelings of others. Choose a question such as “What can we do when someone feels sad?” or “What makes someone feel happy?” Write children’s responses to these questions on a presentation board with sketches for visuals to go along with each idea. This is a helpful way to hear a range of ideas about what influences the emotions of our peers and offers children ideas about what they can do to interact. Keep the board handy for reference and to continue adding more ideas!

5. SELF-LOVE

We all need to remember this one all year long, and especially around Valentine’s Day! Some might feel that this is a selfish idea, however, if we remember to take care of ourselves we will increase our capacity to care for others. How can we teach this idea starting at a young age? Much of it starts with noticing what our children respond to and how we can nurture their emotional wellbeing. Here are a few ideas for how to teach self love:

- Nurture autonomy.Give children space to spend time independently playing and exploring without interruption. Valuing the importance of this solo time is a way of showing children that they can be their own loving companion! When children are very young, this time might be quite brief. Parents/teachers should be prepared to engage with them again when they are ready.

- Create cozy places. Create a cozy place where children can go when they would like some solo space. This is a place for children to go of their own choosing! The Cozy Space can be designed to engage the senses in a calming way, which could include sensory bottles, squishies, scented items, visuals of nature and soft pillows to make it comfortable!

- Day-to-day self-love. Describe how children are caring for themselves when they are eating healthy food. Bathrooming and bathing are also important ways we take care of ourselves which are pivotal at this time in children’s lives. We can cheer children on by saying things such as: “You are really taking care of your body by washing with soap!” Even nap time and night time sleep are ways they take care of their growing bodies, allowing themselves to rejuvenate for more play and learning later!

Valentine’s Day can certainly serve as a catapult to refresh and renew our intentions around love. As a teacher, I have noticed how children embrace the chance to show care for each other when creating these opportunities in the classroom.

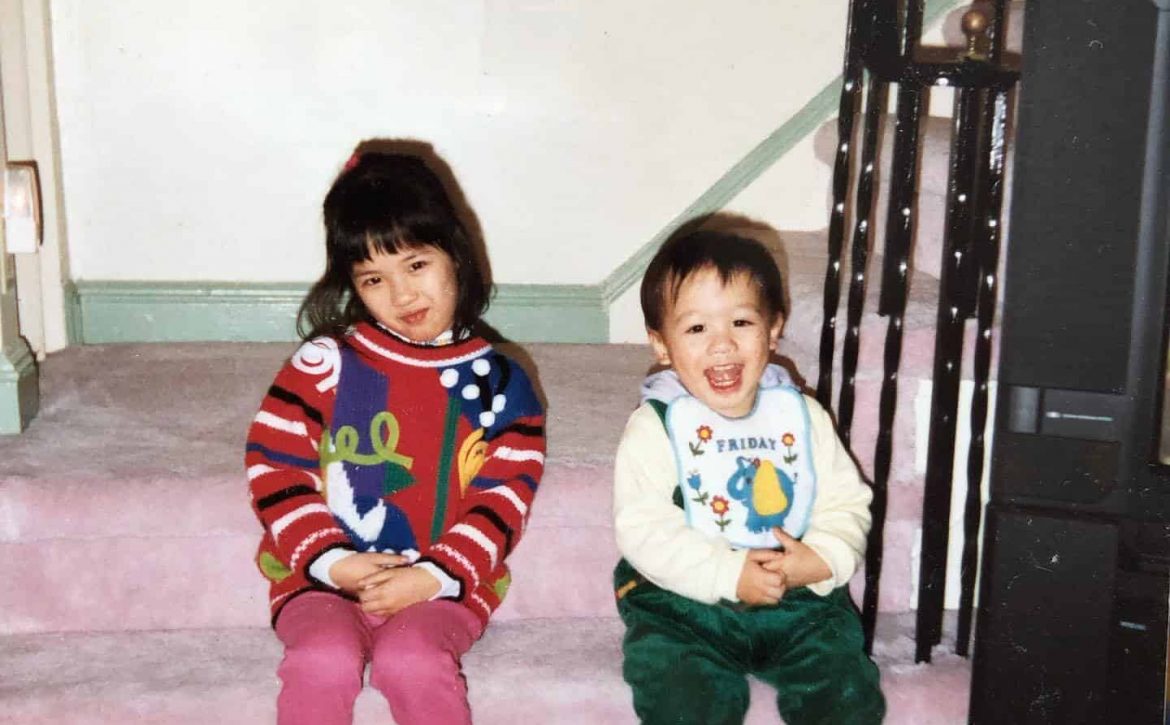

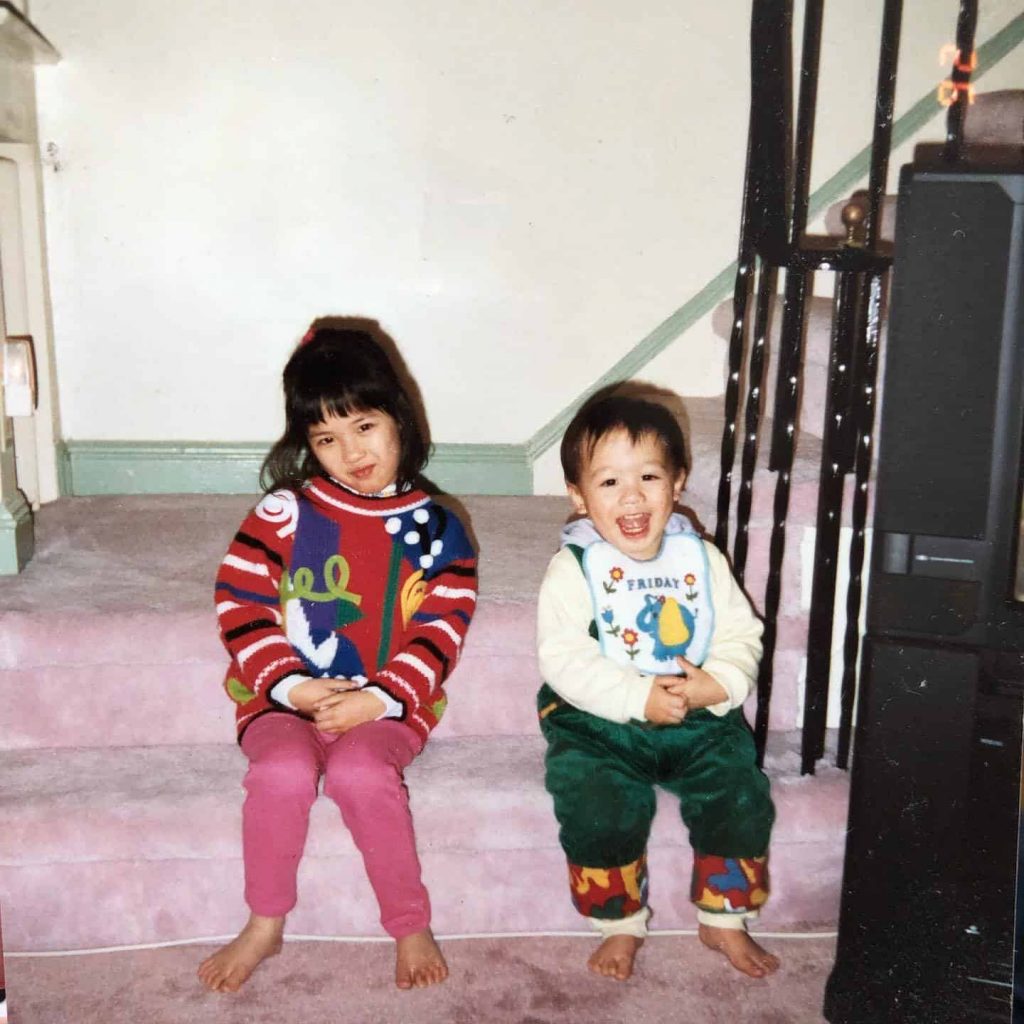

Children also help us to see love and remind us that it is all around us. When my daughter was 3 years old, one day she gently put her pointer finger right between my eyes on what can be referred to as the 3rd eye and said, “love lives here mommy” — love lives in our eyes, our voices and is in our hands to pass along!