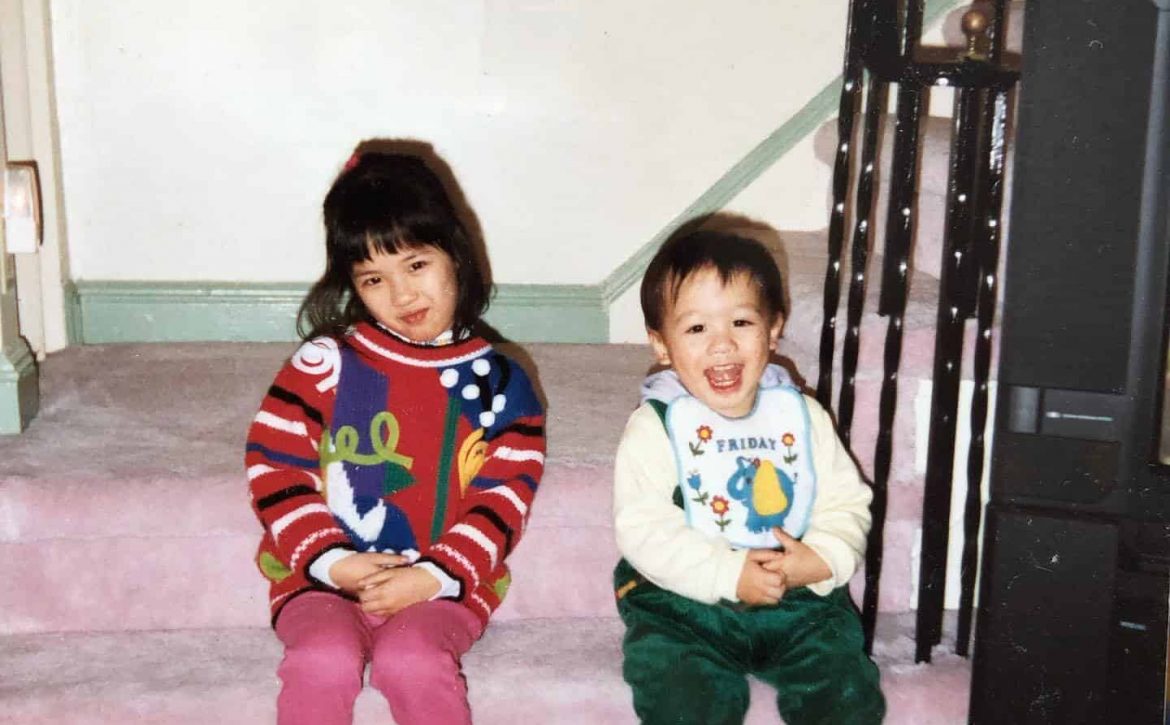

Parenting With a Big Heart: How My Three Year Old’s Comment Helped Us Change Our Family’s Approach to Race

When Auggie was 3, he surprised me with the off-handed comment that “only grownups could have brown skin, and not children.” It really took me aback. We live in NYC after all, a city with so many different kinds of people!

My first impulse was to remind him of the friends he had who were black. But … I could think of one. The more I thought about it, our neighborhood has a lot of white people. Our nursery school has children who speak many languages, whose family come from many different countries, but again, nearly no families of color, or those that look different from him on the outside. He has had black teachers, we have black grown up friends. He didn’t have friends who were children of color, and as preschoolers do, he decided something about the world, based on the information presented to him.

We spent a lot of Auggie’s daily life in largely white spaces — white neighborhoods, white schools. NYC is so diverse and also so segregated. And we hadn’t really talked about race before, because he hadn’t brought it up.

How We Responded

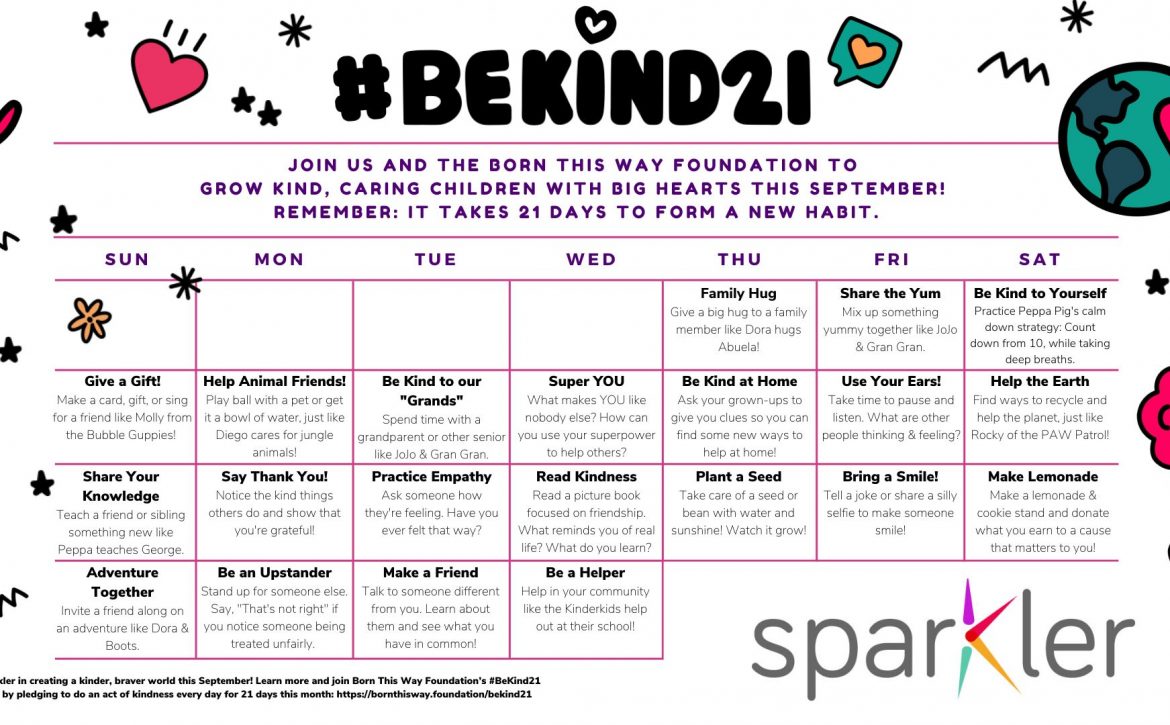

We made some conscious changes based on this initial conversation: visiting more playgrounds and areas of the city more frequently, where children and families did not all look the same. I realized in choosing early picture books for Auggie, I had told myself that most of the characters were animals anyway, so I didn’t need to worry too much about representation. I realize now that when he wasn’t in an environment where there were children of color, books were a primary place we could surround ourselves with diverse friends.

Auggie is 6 now, and we talk about race often, with conversations often motivated by him. While I wished that conversation when he was 3 had been the big shift, it was actually the Black Lives Matter movement in 2020 that did it. We marched, we explained, we talked about all the ways our country isn’t fair for people of color.

“Fair” is very important for the 4-6 set, and it resonated with him. He points out when books leave folks out, or have “old ideas” now. His elementary school was particularly chosen for its diverse student body, and focus on social justice. It really helps me to have a village of supports around him to bring up these conversations again and again. I’m a progressive educator, and always approached a lot of my child’s learning by letting it emerge from him and his interests.

But I learned that these topics may not emerge on their own, particularly if my son is surrounded by others who look only like him.

It’s our job as parents to provide and build a community who is diverse and inclusive, to provoke these conversations, and to point out and stand up ourselves for things that aren’t fair in the world around us.